Real Independence

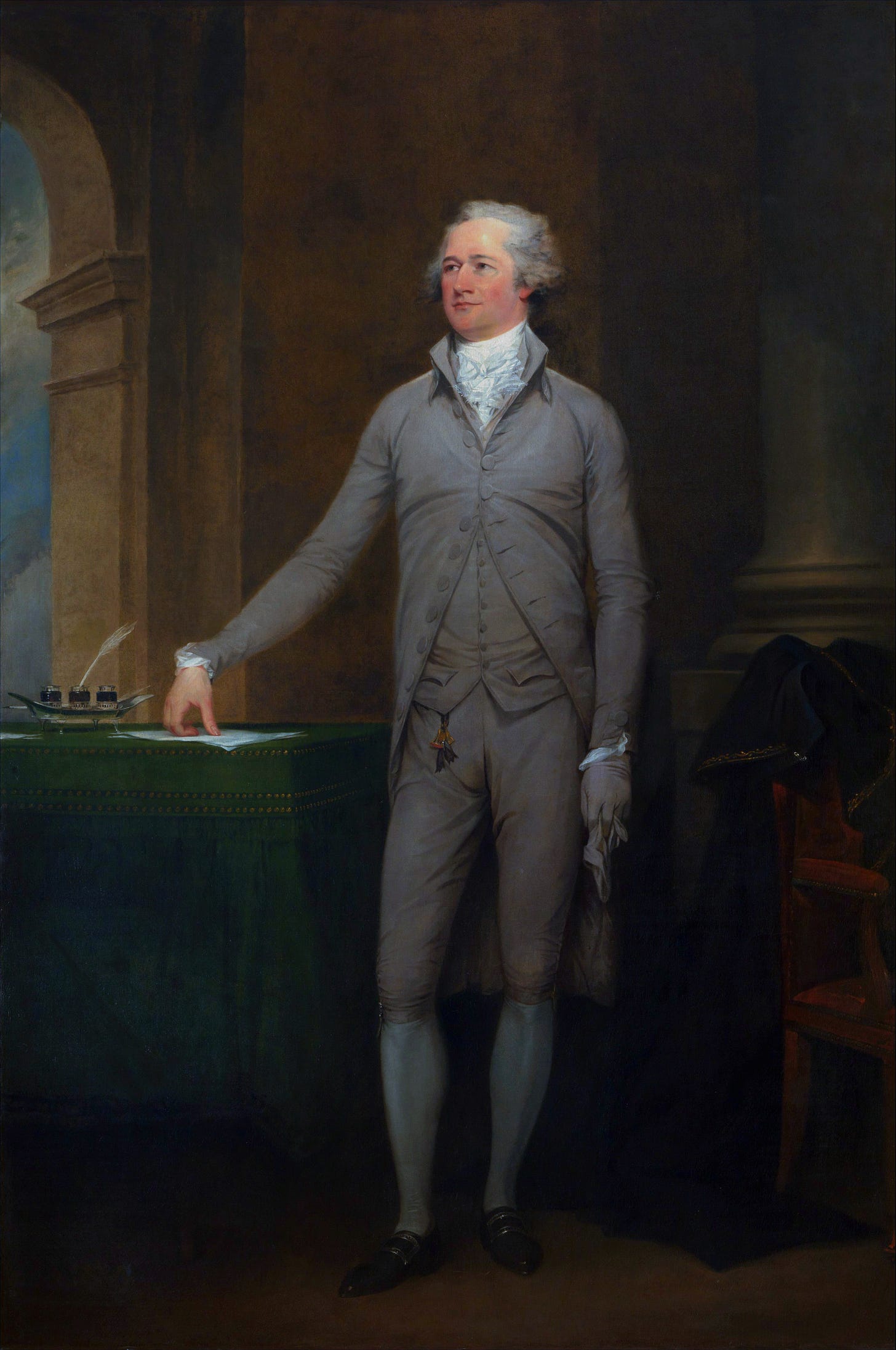

Lessons in National Sovereignty from Alexander Hamilton

And power is more important than wealth. That is indeed the fact. Power is more important than wealth. And why? Simply because national power is a dynamic force by which new productive resources are opened out, and because the forces of production are the tree on which wealth grows, and because the tree which bears the fruit is of greater value than the fruit itself. Power is of more importance than wealth because a nation, by means of power, is enabled not only to open up new productive sources, but to maintain itself in possession of former and of recently acquired wealth, and because the reverse of power—namely, feebleness—leads to the relinquishment of all that we possess, not of acquired wealth alone, but of our powers of production, of our civilisation, of our freedom, nay, even of our national independence, into the hands of those who surpass us in might, as is abundantly attested by the history of the Italian republics, of the Hanseatic League, of the Belgians, the Dutch, the Spaniards, and the Portuguese.

Friedrich List, The National System of Political Economy1

The unity of government which constitutes you one people is also now dear to you. It is justly so; for it is a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home, your peace abroad, of your safety, of your prosperity, of that very liberty which you so highly prize.

George Washington, Farewell Address2

Scenario: your nation just won its independence in a war from the mother country on the other side of the ocean; you have a gaggle of independent republics that aren’t eager to work together but are filled with people related by blood, by language, by religion, and by political heritage; you don’t have any manufactures, forcing you to import heavily from the former mother country; and your weak national government has a large debt to pay off without the power to lay taxes or consolidate the debt of the independent states. Your country can’t even produce weapons of war and has to import them from the very country you just won independence from!

How does a statesman advance his nation beyond the submissive colonial state and achieve real independence? This historical inquiry will provide manifold insight into America’s present crises and what possibilities lie for us in the domain of statecraft.

The first thing you need is a functioning government that has authority to prevent wars between the states, levy tariffs, regulate the currency, build an army and navy, build infrastructure, and conduct foreign diplomacy. Easier said than done.

Once that’s set up you need to find a way to get factories built and money circulating so that you have enough resources with which to defend yourself from invaders and avoid dependence on imports from potentially hostile nations. That’s what tariffs and a national bank are for.

The basic rundown on tariffs is as follows: if you want your country to develop a manufacturing base, you need to make sure other countries with superior manufacturing techniques can’t just flood your country with cheap goods, driving your upstart factories and workshops out of business, and leaving you dependent on said hostile foreign power. Another danger in having no industry is that, to pay for the excess of imports over exports, money in the form of gold (when they still used that), and debts, are sent to the foreign nation, draining your country of circulating medium, bringing chronic deflation, grinding business to a halt. The answer to this problem is tariffs. It brings up the cost of imports to at least the level at which domestic manufacturers can sell their goods, putting the domestic manufacturers at an equal footing with the foreign within the home market. In time as technique improves, inefficiencies are ironed out, and economies of scale grow up, the cost of home-produced goods lowers, and the quality rises, to the level of the competing foreign goods. The income from the tariffs can be used to subsidize businesses to help offset startup costs and grow past infancy more quickly. When all’s said and done, among numerous other benefits, your nation will be able to afford its imports by paying with exports instead of debt; and from the perspective of statecraft, being able to manufacture war munitions is critical. Equally important as these advantages is the fact that the diversification of the home market will contribute to the growth and quality of all other sectors of the home market, whether agricultural, manufacturing, or mercantile—a harmony of interests. This is the theory Hamilton put forward in his Report on Manufactures in 1791, serving as the starting point for the American School of political economy, and which has been proven successful in practice in many cases, not least of which was our own.

Creating a uniform currency and a credit system is necessary to ensure that productive businesses have sufficient funds to get started and to keep up with regular expenses. Banks can serve this purpose, providing loans which can circulate as a paper currency. Its stability and ease of use will attract foreign investment, making the country a magnet for capital from the other centers of commerce, paving the way for the nation to reach economic preeminence. Finance is the most important weapon of war, loans of foreign and domestic origin often being essential to military victory. Ideally this bank would be run with strict government oversight to prevent foreigners and sefish private interests from taking control of the money creation power for unfair gain or undermining the interests of the nation. A national bank will also avoid the confusion inclement to letting local and state banks monopolize the issuance of money, as these loans in earlier times were of limited utility in interstate commerce. With branches around the country, business can be conducted smoothly between clients in distant regions, serving the double purpose of aiding prosperity and fostering national feeling, binding the people together (see: etymology of “commerce”). Ideally money would simply be issued by the government in a definite amount in the form of paper, but historically that comes a bit later.

This isn’t a bunch of theoretical speculation. This was the thought process and actual practice of Alexander Hamilton and George Washington in their plans to shape the American government; these in truth being a set of obstacles that every nation needs to overcome in some form to survive. Hamilton was a 19th century man living in the 18th century. He saw these fledgling states in a global geopolitical context, as a nation among predatory nations. Of all individuals it’s to him, as well as George Washington, that we owe the existence of our unified country and the establishment of the institutions essential to real independence. After fighting in the War of Independence, famously leading a bayonet charge at the Battle of Yorktown, he began his law career and then his political career in congress, the dream of a fully united America fixed in his mind. Soon he became instrumental in getting a proper federal government established. In his capacity as the nation’s first Secretary of the Treasury he built the nation’s currency and credit system from scratch, as well as the real and theoretical foundations for America’s industrial revolution. His creative efforts in the realm of politics culminated in building both a government and a nation. It took several decades for the consensus in American high politics to catch up to Hamilton’s and Washington’s foresight. Jefferson, a brilliant man in his own right, lagged behind his rival for many years before ultimately settling on similar conclusions.

Another American hero and visionary, Henry Clay, looking back in 1840 summed up the perilous economic situation inherited by the newly independent nation:

What was our condition during the colonial state, when, with the exception of small amounts of government paper money, we had no currency but specie, and no banks? Were we not constantly and largely in debt to England? Was not our specie perpetually drained to obtain supplies of British goods? Do you not recollect that the subject of the British debts formed one of those matters which were embraced in the negotiations and treaty of peace, which terminated the revolutionary war? And that it was a topic of angry and protracted discussion long after, until it was finally arranged by Mr. Jay's treaty of 1794?3

To get things started, you need to solve the basic issue of mustering up the collective manpower, brainpower, and natural resources of the nation—a federal union that can hold the states together to make binding decisions on behalf of the whole nation, without the confused interference of the many state legislatures. This undertaking was more or less realized in the Constitution handed down to us. Hamilton, recognizing the need for a fully functioning government, busied himself from 1786 in setting up a constitutional convention to replace the unworkable Articles of Confederation. Though not heavily involved in the drafting of the constitution itself, once completed, Hamilton was its loudest proponent, and, in the heated debates surrounding its ratification, its most unyielding advocate. This was in spite of the fact that Hamilton believed the Constitution to be deeply flawed, being a creature of compromise and not reaching his ideal by any means. In fact he wanted the government to be much more powerful, more vigorous, and less democratic. But a federal union of some kind was absolutely essential, and it was the best shot we had at getting a functioning government, so he took it as is and ran with it. The Federalist Papers, a masterpiece of political thought, written in large part by Hamilton, were published in newspapers to explain to the people why the union was necessary and how it would benefit them. Many political problems pressing us today have already been solved in this work, its insights ignored by a generation occupied with alien ideas and foreign thought-leaders. Hamilton presents a vision of an American Leviathan rising to take its place in the sun, though menaced in its infancy by powerful foreign rivals and self-interested native strivers. Henry Cabot Lodge in his seminal biography of the great statesmen tells us of Hamilton’s Herculean effort to persuade the New York state legislature and Governor George Clinton, among the most stubborn holdouts against the new Constitution, to ratify it, engaging in constant vigorous debate, eventually forcing the governor to admit defeat, and swinging the support of the state convention from two-thirds against, to a slim majority in its favor4. The opponents of the Constitution did not generally have any alternative plan for the nation; they mostly opposed it on grounds of stubbornness and a desire to keep their personal local power as concentrated as possible, often decrying as tyranny powers granted to the federal government that states already wielded more strongly. It’s no wonder, then, that this resistance could not hold out long.

Contrary to ideas common today among the American right, the Federalists believed tyranny to spring from unchecked aristocracies, foreign corruption, and a lack of restraint of popular passions, not strong governments as such. A properly balanced government with definite but unchallenged powers, they thought, is the greatest bulwark against these primary sources of oppression, but a weak government with excessive democracy is a sponge for foreign contamination and chaos of all kinds. The skepticism of strong government was more the domain of Jefferson and his supporters, who later repented of this folly, leaving modern libertarians with no excuse. As early as 1780, Alexander Hamilton saw the most dangerous threat facing the nation in the fact that “the common sovereign will not have power sufficient to unite the different members together, and direct the common forces to the interest and happiness of the whole”5, reflecting a view of the role of government from which he did not deviate in the course of his life. If the 13 colonies did not band together, Hamilton and the Federalists warned, foreign powers would easily play one confederacy against another, providing Europe with a foothold on this continent, reducing us to the chronic bloodshed and alien overlordship that most of Europe had tragically been acquainted with from its ancient past.

A schism once introduced, competitions of boundary and rivalships of commerce will easily afford pretexts for war. European powers may have inducements for fomenting these divisions and playing us off against each other.

Continentalist No. III, 1781

The need for a vigorous executive in particular is demonstrated in stark terms in Federalist No. 22:

One of the weak sides of republics, among their numerous advantages, is, that they afford too easy an inlet to foreign corruption. An hereditary monarch, though often disposed to sacrifice his subjects to his ambition, has so great a personal interest in the government, and in the external glory of the nation, that it is not easy for a foreign power to give him an equivalent for what he would sacrifice by treachery to the state. The world has accordingly been witness to few examples of this species of royal prostitution, though there have been abundant specimens of every other kind.6

In Hamilton’s ideal this meant a single President, chosen by electors who themselves were chosen by electors, serving for life during good behavior, with absolute veto power over the rest of the government—one man, representing the whole nation in himself, invested with the power to redirect the course of the nation when the popular and aristocratic branches of government get out of hand, as they can easily degenerate into mob democracy or oligarchic tyranny. This aim was not fully realized in the executive branch defined in the constitution, a shortcoming John Adams bitterly lamented. But James Wilson, the principal author of the executive branch in our constitution, used similar arguments to Hamilton in justifying a sole executive, as opposed to the proposals by others at the convention to make the executive branch a committee or temporary role appointed by congress, which would have relegated the president to the status of a mere doge or puppet, having no authority other than what is granted to him at congress’ discretion. A single executive is also more personally accountable than a group of co-executives, a fact of particular importance for a role that requires quick and decisive action. This plan for the executive branch was controversial for its similarity to monarchy, which became less popular as distaste for everything English grew stronger. The idea of the separation of powers was drawn from the traditional English constitution, where democracy (house of commons in England, house of representatives in the US), aristocracy (house of lords in England, the Senate in the US), and monarchy were all incorporated, each branch of government representing one of the three groups of society: the many, the few, and the one. The entire nation was to be consulted in important decisions affecting them all. In 1780 Hamilton noted:

Congress is properly a deliberative corps and it forgets itself when it attempts to play the executive. It is impossible such a body, numerous as it is, constantly fluctuating, can ever act with sufficient decision, or with system. Two thirds of the members, one half the time, cannot know what has gone before them or what connection the subject in hand has to what has been transacted on former occasions. The members, who have been more permanent, will only give information, that promotes the side they espouse, in the present case, and will as often mislead as enlighten. The variety of business must distract, and the proneness of every assembly to debate must at all times delay.7

Hamilton was aware that for a government to maintain its sovereignty it must be strong enough to hold its own among the nations of the world. Excess democracy makes the government weaker, more susceptible to fleets of popular passion, more sluggish, unable to respond with the needed force of will in the event of crisis. In a speech at the Constitutional Convention, he was reported as saying:

Those Persons who have had frequent Opportunities of conversing with the Representatives of European Sovereignties know they are very anxious to perpetuate our Democracies. This is easily accounted for—Our weakness will make us more manageable. Unless your Government is respectable abroad your Tranquility cannot be preserved.11

Shortly before his death, some New England Federalists were plotting to secede from the union and form a northern confederacy in reaction to the incompetence of the Jefferson administration. In his last known letter before his fateful duel, Hamilton sternly rebuked this conspiracy, in conformity with his lifelong nationalist views:

I will here express but one sentiment, which is, that Dismembrement of our Empire will be a clear sacrifice of great positive advantages, without any counterballancing good; administering no relief to our real Disease; which is DEMOCRACY, the poison of which by a subdivision will only be the more concentered in each part, and consequently the more virulent.12

In the realm of finance, Hamilton came up with a plan to pay back the nation’s war debts to keep the nation in good standing to ensure that future opportunities for loans would not be hindered and that the nation’s honor and moral standing not be blemished. He proposed and later won the political battle to have the federal government assume the funding of the state debts to ensure they would be paid in a regular manner. But the higher aim of this scheme was “to cement more closely the union of the states; to add to their security against foreign attack; to establish public order on the basis of an upright and liberal policy.”8 In his report on public credit he also explained how a funded debt serves to augment our insufficient money supply by allowing the outstanding interest-bearing government bonds to circulate as a form of payment equivalent to money (monetizing the debt), something which would be aided by the National Bank. Hamilton’s brilliance as a financier showed forth in not only the extinguishment of the debt but also in the use of finance as a tool to build a nation. This is particularly impressive when you consider that at this time matters of finance were less generally well understood than today.

Alexander Hamilton’s economic nationalist ambitions also shined through in his plan for a National Bank. To even get the bank signed into law, he had to justify it legally under the Constitution, which he achieved by inventing of the doctrine of implied powers. The rationale being that the federal government should have unlimited power to accomplish its enumerated ends—in this case, providing for the general welfare of the nation and fulfilling Congress’ duty to regulate the currency. Hamilton’s reasoning successfully persuaded President Washington and in 1791 he signed the Bank bill into law. Without the implied powers construction our government would have proven feeble in the face of the tasks set before it; it breathed life into what would have otherwise been a dead letter. The existence of the bank would encourage people to take gold and silver out of storage to be deposited in the bank, making the formerly dead stock the basis of a lively circulating medium. In addition to adding to the circulating medium and nurturing real economic growth by providing a safe means of productive investment, one major purpose for chartering a National Bank was to strengthen the government:

The reason is obvious: The capitals of a great number of individuals are, by this operation, collected to a point, and placed under one direction. The mass, formed by this union, is in a certain sense magnified by the credit attached to it: And while this mass is always ready, and can at once be put in motion, in aid of the Government, the interest of the bank to afford that aid, independent of regard to the public safety and welfare, is a sure pledge for its disposition to go as far in its compliances, as can in prudence be desired. There is in the nature of things, as will be more particularly noticed in another place, an intimate connection of interest between the government and the Bank of a Nation.9

The multiple branches of the bank and consequent regularity of currency across the country would contribute to the far-sighted goal of uniting the people of America into one solid block, increasingly free of sectional prejudices. The construction of interstate roads and canals to quicken communication and transportation, a function more suited to a national government than to the states individually, would serve the same purpose, this latter goal being a favorite of Washington. The individual investors in bank stock would be personally interested in the development and financial stability of the nation. Uniting the people to one another and to their government—this is nationalism in action.

The bank wasn’t perfect from a modern standpoint, though Hamilton wasn’t trying to make an original or perfect bank, but rather one based on tried and true models like the Bank of England. It was based on a fractional reserve system, which is where the bank loans out more money than it has in deposits, in hopes that everyone won’t cash out at the same time. A better system would be to simply have the government create a fixed amount of paper currency to be spent and lent into circulation and increased either at a ratio to population growth or economic growth to avoid inflation or deflation. Such monetary systems were later devised by men like Edward Kellogg, Alexander Del Mar, and Georg Friedrich Knapp who focused on fiat currency as the standard. Fiat currency was implemented in the United States in the form of the greenbacks under Lincoln, another statesman of the Hamiltonian tradition, to great success. The biggest issue with metal-based currency or any other commodity-based currency is the tendency for a few private individuals to horde the bulk of the supply, leaving them with power over the world’s money supply, an issue thoroughly documented by Del Mar, Brooks Adams, Knapp, and several others. In Hamilton’s time this method of full state control over money hadn’t been tried yet. Hamilton’s bank was to be privately owned but subject to strict congressional scrutiny. Unaccountable private control of the money creation power entails surrendering of political sovereignty from the government to either the bankers or foreign governments, things to be avoided at all costs. Hamilton understood this, which is why, though privately owned, the bank was accountable to congress and intended not to enrich a few moneychangers at the nation’s expense. “It is to be considered,” Hamilton wrote, “that such a Bank is not a mere matter of private property, but a political machine of the greatest importance to the State.”10

The Report on Manufactures, summarized in part above, is arguably the most important and far-sighted work of our statesman. The author knew that the full realization of the plan was many years away, but the rationale was put before the world as soon as possible. The Founders were in no wise averse to government interference in the economy, no matter what neoconservatives and RINOs would have you believe. Who can look at our current dependence on Chinese manufactures and not see a parallel to America’s relation to Britain in the early part of our republic’s history? A quick glance of the history of great powers demonstrates that material prosperity and political power are mutually dependent and the one can almost never be found without the other. For the nation to prosper the government needs to use its power to increase the wealth of the country, the wealth being wielded as power itself—greater population and greater productivity of labor, yielding greater leverage over other nations in negotiations, and in the last resort, greater means to win wars. A rich nation can be very powerful; a poor nation is necessarily weak. If you have to import military supplies from hostile countries, as Hamilton pointed out in his Report, and America learned in the War of 1812, you’re in serious danger. A home market is a more secure and stable vent for excess goods, and guarantees to your nation the full profits of commerce, as opposed to foreign trade, which is subject to vicissitudes of war, trade restrictions, and fluctuations in demand. Therefore outsourcing of manufacturing industry is contrary to long-term national sovereignty, as manufacturing is essential to the wealth of a nation above and beyond the small wealth possible in a mere agricultural state. Artificial labor in the form of machines increases the productivity of labor by orders of magnitude:

The employment of Machinery forms an item of great importance in the general mass of national industry. ’Tis an artificial force brought in aid of the natural force of man; and, to all the purposes of labour, is an increase of hands; an accession of strength, unincumbered too by the expence of maintaining the laborer. May it not therefore be fairly inferred, that those occupations, which give greatest scope to the use of this auxiliary, contribute most to the general Stock of industrious effort, and, in consequence, to the general product of industry?13

This fact was also emphasized by political economists of the American School like Henry Charles Carey and Erasmus Peshine Smith, and statesmen like Henry Clay. In 1820 Clay estimated that “the combined force of all the machinery employed by Great Britain, in manufacturing, is equal to the labor of one hundred millions of able-bodied men” and that “machine labor will stand to manual labor, in the proportion of one hundred to two.”14

Tariffs (taxes on imports) are among the primary means by which state power can be wielded to manage the flow of trade to increase national wealth, and Hamilton urged his countrymen to take up the opportunity to do so. A tariff to encourage manufactures was among the first acts signed into law under the constitution, with the approval of President Washington (the “Hamilton Tariff”). The Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures, a public-private partnership begun during Washington’s administration under Hamilton’s direction, achieved modest success, and helped kickstart America’s industrial revolution.

There are some, who maintain, that trade will regulate itself, and is not to be benefitted by the encouragements, or restraints of government. Such persons will imagine, that there is no need of a common directing power. This is one of those wild speculative paradoxes, which have grown into credit among us, contrary to the uniform practice and sense of the most enlightened nations. Contradicted by the numerous institutions and laws, that exist every where for the benefit of trade, by the pains taken to cultivate particular branches and to discourage others, by the known advantages derived from those measures, and by the palpable evils that would attend their discontinuance—it must be rejected by every man acquainted with commercial history. Commerce, like other things, has its fixed principles, according to which it must be regulated; if these are understood and observed, it will be promoted by the attention of government, if unknown, or violated, it will be injured—but it is the same with every other part of administration.

Continentalist No. V, 1782

There may, on the other hand, be a possibility of opening new sources, which, though accompanied with great difficulties in the commencement, would in the event amply reward the trouble and expence of bringing them to perfection. The undertaking may often exceed the influence and capitals of individuals; and may require no small assistance, as well from the revenue, as from the authority of the state.

Continentalist No. V, 1782

I’ll briefly outline the problems with economic liberalism. Free trade ideology, championed by David Ricardo and the Manchester School in England, assumes that the whole world is one country, and that it is always in a country’s interest to allow perfect freedom of trade with all others. The liberal school ignored nations and focused on the interest of individuals and humanity generally, missing the gap that nations fill in between. This doctrine was harshly criticized as unhistorical and overly theoretical by Friedrich List, a Hamiltonian figure who led the effort for economic unification of Germany, as well as the whole American School from Hamilton to Henry Carey, Erasmus Peshine Smith, Robert Ellis Thompson, et al. Britain did not become an economic giant by following free trade—they used a protective system (mercantilism) to nourish their infant industries against their competitors on the continent. It was only once England’s manufacturing powers grew to surpass all other nations’ that she began to preach free trade to the world—something which benefitted England and no one else. It was meant only to furnish her with cheap raw materials and drive all potential competing manufacturers out of business, reducing all other nations to a primitive agrarian state, dependent on England. “British free trade,” as Henry Clay and the other advocates of the American System called it, was the arch enemy of American sovereignty throughout the entire 19th century, even to this day. British liberal economics assumes and encourages class war, that the rich should plunder the poor, a civilizationally suicidal outlook later inverted by Marx to similarly destructive effects. Nationalism and class harmony, growth in wealth and comfort for the capitalist and his workers with growing power to exploit nature rather than each other, with the nation as the economic unit, were the outlook of Hamilton and his successors—in a word, Nationalism.

Another important observation from the Report on Manufactures is how diversification of employments increases national wealth by taking better advantage of the different skills and talents of different individuals in the national community:

This is a much more powerful mean of augmenting the fund of national Industry than may at first sight appear. It is a just observation, that minds of the strongest and most active powers for their proper objects fall below mediocrity and labour without effect, if confined to uncongenial pursuits. And it is thence to be inferred, that the results of human exertion may be immensely increased by diversifying its objects. When all the different kinds of industry obtain in a community, each individual can find his proper element, and can call into activity the whole vigour of his nature. And the community is benefitted by the services of its respective members, in the manner, in which each can serve it with most effect.15

A nation that specializes in merely cultivating a few types of products for the purpose of export (like Britain’s colonies, and the American South up to the Civil War) cannot be rich. Having everyone work in, e.g., agricultural labor, results in a large amount of wasted labor, the enemy of efficiency and wealth. Henry Charles Carey in the mid-19th century wrote extensively on this issue, noting that the long periods of yearly downtime in farm work is easily filled with factory labor, adding wealth and dignity to formerly languishing communities. Trains save hours and days in transporting crops to market; metal fence posts save time and labor in replacing wooden fence posts that rot; building a clothes mill in a cotton-growing area saves money that would otherwise be wasted in transportation to faraway workshops, gives the inhabitants something to do with the times between sowing and harvest, and yields additional income and more and cheaper clothing to the community. At scale these savings are a treasure trove to the nation (for more, see Carey’s The Harmony of Interests). This is what made the political battle to give government support to industrialization so vital to our national survival.

Hamilton summed up his economic nationalist ambition in The Federalist No. 11:

Let Americans disdain to be the instruments of European greatness! Let the Thirteen States, bound together in a strict and indissoluble union, concur in erecting one great American system, superior to the control of all transatlantic force or influence, and able to dictate the terms of the connexion between the old and the new world!16

The most underrated, and, from the perspective of present-day American nationalists, the most immediately practicable, dimension of Hamilton’s legacy, is nativism. Hamilton was the father of American nativism, showing extreme disdain and jealous anxiety for foreign influence. Our national sovereignty cannot be maintained if the institutions imbued with power (government, finance, media) become swamped with individuals with foreign loyalties, as they are now. And the entrance of large amounts of aliens will involve the importation of alien views of government, law, religion, and society. The national character will be blunted, possibly even smothered; and our government will be pulled into foreign entanglements not in our interest.

The information which the address of the Convention contains, ought to serve as an instructive lesson to the people of this country. It ought to teach us not to over-rate foreign friendships—to be upon our guard against foreign attachments. The former will generally be found hollow and delusive; the latter will have a natural tendency to lead us aside from our own true interest, and to make us the dupes of foreign influence. They introduce a principle of action, which in its effects, if the expression may be allowed, is anti-national. Foreign influence is truly the GRECIAN HORSE to a republic. We cannot be too careful to exclude its entrance. Nor ought we to imagine, that it can only make its approaches in the gross form of direct bribery. It is then most dangerous, when it comes under the patronage of our passions, under the auspices of national prejudice and partiality.17

The opinion advanced in the Notes on Virginia is undoubtedly correct, that foreigners will generally be apt to bring with them attachments to the persons they have left behind; to the country of their nativity, and to its particular customs and manners. They will also entertain opinions on government congenial with those under which they have lived, or if they should be led hither from a preference to ours, how extremely unlikely is it that they will bring with them that temperate love of liberty, so essential to real republicanism? There may as to particular individuals, and at particular times, be occasional exceptions to these remarks, yet such is the general rule. The influx of foreigners must, therefore, tend to produce a heterogeneous compound; to change and corrupt the national spirit; to complicate and confound public opinion; to introduce foreign propensities. In the composition of society, the harmony of the ingredients is all important, and whatever tends to a discordant intermixture must have an injurious tendency.18

To render the people of this Country as homogeneous as possible must lend as much as any other circumstance to the permanency of the Union & prosperity.19

Particular attachment to any foreign nation is an exotic sentiment which, where it exists, must derogate from the exclusive affection due to our own country.20

We are labouring hard to establish in this country principles more and more national and free from all foreign ingredients—so that we may be neither “Greeks nor Trojans” but truly Americans.21

In the life and work of Alexander Hamilton we find the essentials of statecraft and the foundations of national sovereignty. An American statesman worthy of the title would do well to familiarize himself with the man who above all others made our existence possible, whose person is virtually synonymous with the form of government that propelled our people to towering heights. Hamilton’s ideas didn’t die with him, though. The vision was kept alive with the Whig party of Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John Quincy Adams, and the Republican party of Lincoln and McKinley—the vision of a nation with all classes and sections united under one government, growing in wealth and dignity with a paternal nourishing of domestic industry, wielding all available human and natural resources for the furtherance of the nation, disdaining to be instruments of foreign greatness, a vision that only began to dim as the American people lost much of their political sovereignty in the early 20th century. We Americans are lucky to have such brilliant lights in our own past; though there have been similar figures in other nations who overcame, or tried to overcome, similar problems of disunity and building of a nation such as Jean-Baptiste Colbert in France, and Friedrich List and Bismarck in Germany, who are also worthy of attention. Americans today face challenges of a different nature no less titanic than those faced by the founders of this nation, but the principle of nationality still serves as the guiding lodestone on our path to renewed liberty. At the beginning, as now, the only way for the American people to survive was to establish and hold fast to a vigorous government made up exclusively of loyal American people, free from all foreign ingredients. I will conclude with the judgement of Henry Cabot Lodge:

The other great idea of which he was the embodiment was that of nationality. No other man of that period, except Washington, was fully imbued with the national spirit. To Hamilton it was the very breath of his public life, the essence of his policy. To this grand principle many men, especially in later times, have rendered splendid services and made noble sacrifices; but there is no single man to whom it owes more than to Hamilton. In a time when American nationality meant nothing, he grasped the great conception in all its fullness, and gave all he had of will and intellect to make its realization possible. He and Washington alone perceived the destiny which was in store for the republic. For this he declared that the United States must aim at an ascendant in the affairs of America. For this he planned the conquest of Louisiana and the Floridas, and, despite the frowns of his friends, rose above all party feelings and sustained Jefferson in his unhesitating seizure of the opportunity to acquire that vast territory by purchase. To these ends everything he did was directed, and in his task of founding a government he also founded a nation. It was a great work. Others contributed much to it, but Hamilton alone fully understood it.22

Further reading:

Henry Cabot Lodge: Alexander Hamilton, 1882

John T. Morse, Jr.: The life of Alexander Hamilton in 2 vols., 1876

William S. Culbertson: Alexander Hamilton, an Essay, 1910

Bibliography:

1. Friedrich List, The National System of Political Economy. Translated by Sampson S. Lloyd. (London: Longmans, Green, and Company, 1841), p. 37. https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/lloyd-the-national-system-of-political-economy.

2. George Washington, Farewell Address (1796), https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/Washingtons_Farewell_Address.pdf

3. Calvin Colton, Life and Times of Henry Clay Vol. II (New York: A. S. Barnes & Co., 1846), https://archive.org/details/lifetimesofhenry02colt/page/56/mode/2up, 57

4. Henry Cabot Lodge, Alexander Hamilton, (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1910), p. 49-56, 69-75, https://archive.org/details/alexanderhamilto00lodgrich/page/48/mode/2up.

5. Alexander Hamilton. “From Alexander Hamilton to James Duane, [3 September 1780]”, Founders Online. National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0838.

6. Alexander Hamilton, “Federalist No. 22”, Library of Congress, 1787. https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/text-21-30#s-lg-box-wrapper-25493335.

7. Alexander Hamilton. “From Alexander Hamilton to James Duane, [3 September 1780]”, Founders Online. National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0838.

8. Alexander Hamilton. “Report Relative to a Provision for the Support of Public Credit, [9 January 1790]”, Founders Online. National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-06-02-0076-0002-0001.

9. Alexander Hamilton. “Final Version of the Second Report on the Further Provision Necessary for Establishing Public Credit (Report on a National Bank), 13 December 1790.” Founders Online. National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-07-02-0229-0003.

10. Hamilton, Alexander. “Final Version of the Second Report on the Further Provision Necessary for Establishing Public Credit (Report on a National Bank), 13 December 1790.” Founders Online. National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-07-02-0229-0003.

11. “Constitutional Convention. Remarks on Equality of Representation of the States in the Congress, [29 June 1787].” Founders Online. National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0109#ARHN-01-04-02-0109-fn-0001.

12. Alexander Hamilton. “From Alexander Hamilton to Theodore Sedgwick, 10 July 1804.” Founders Online. National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-26-02-0001-0264.

13. Alexander Hamilton. “Alexander Hamilton’s Final Version of the Report on the Subject of Manufactures, [5 December 1791].” Founders Online. National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-10-02-0001-0007.

14. Life and Speeches of Henry Clay Vol. 1, ed. James B. Swaine (New York: Greeley & McElrath, 1843), p. 143-144, https://archive.org/details/lifespeechesofhe01inclay/page/142/mode/2up.

15. Alexander Hamilton. “Alexander Hamilton’s Final Version of the Report on the Subject of Manufactures, [5 December 1791].” Founders Online. National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-10-02-0001-0007.

16. Alexander Hamilton, “Federalist No. 11”, Library of Congress, 1787. https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/text-11-20#s-lg-box-wrapper-25493283.

17. Alexander Hamilton. “Pacificus No. VI, [17 July 1793].” Founders Online. National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-15-02-0081.

18. Alexander Hamilton. “The Examination Number VIII, [12 January 1802].” Founders Online. National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-25-02-0282.

19. Alexander Hamilton. “Draft of George Washington’s Eighth Annual Address to Congress, [10 November 1796].” Founders Online. National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-20-02-0255.

20. Alexander Hamilton. “From Alexander Hamilton to Thomas Lloyd Moore, 6 October 1799.” Founders Online. National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-23-02-0462.

21. Alexander Hamilton. “From Alexander Hamilton to Rufus King, 16 December 1796.” Founders Online. National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-20-02-0285.

22. Henry Cabot Lodge, Alexander Hamilton, (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1910), p. 178-179, https://archive.org/details/alexanderhamilto00lodgrich/page/278/mode/2up.

Excellent article. I am familiar with the subject matter and found nothing I disagreed with or thought was unfair. I, of course, agree with Hamilton and List and Carey. It is blindingly obvious to me.

There was one thing you mention that is new to me: your small section on Hamilton and fractional reserve banking. Am I right that you think Hamilton would have preferred a "pure" fiat currency? But that he advocated one out of expediency and his spirit of compromise?

We are all quite busy, but I would very much like to read more of your thoughts on this subject.

PS. I appreciate the amount of work it takes to write something like this post. Fwiw, I think you succeeded and the effort was worth it.

What is your take on Lyndon LaRouche? I was told my whole life he was a “crazier commie” but what you are say it seems similar to LaRouche’s ideas.